Here’s a conundrum.

In over 20 years as a recruiter, I’ve only twice persuaded a candidate to move for

less money. One was a KPMG partner who took a role with a not-for-profit and

the other was a successful investment banker who wanted to move back to his

native South Africa. But if I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard a candidate say

something along the lines of “of course, money’s not the most important thing”, I’d

probably have retired from recruitment many years ago.

In other words, it rather seems as though money is the most important thing.

This paradox is worth investigating for two reasons. Firstly, much of the world is

suffering a cost-of-living crisis. Secondly, there is an opinion abroad that the various

lockdowns have endowed us all with a more enlightened view of life and work.

According to this narrative, we now care less about money and more about such

things as culture, inclusivity and corporate purpose.

But how true is this paradigm? Can hiring managers really attract top talent without

offering top pay? And if so, what specifically are candidates looking for instead?

We attempted to answer these questions by asking 200 candidates a simple

question: If you were offered a new role, what would be your most important

consideration – the pay, the brand, the role or the culture?

The results, we think, make for interesting reading. Here are our top five takeaways

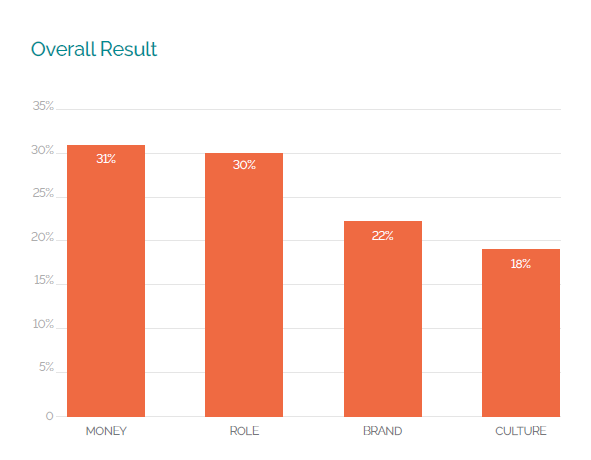

1. Money is most likely to be a candidate’s top priority, but workers are still three times as likely to prioritize something other than money.

A cynic might interpret the graphic above as proof positive that the world’s workers

are still primarily motivated by cold, hard cash. And it’s true, ‘money’ was selected

by our source pool more times than any other answer. But two things are worth

pointing out. Firstly, the results are pretty damn close. Secondly, if we flip the

results on their head, we observe that 69% of respondents said something other

than money. That means any employer looking to attract top talent merely by

paying top whack, could be in for a nasty surprise. Nearly three quarters of their

candidate pool is likely to be more interested in . . . well, what exactly?

This is where the results get really interesting. The fact is, there is no runaway

winner (or distant loser) among the four rival options – brand, pay, culture, role.

That places recruiters in a quandary because they are unable to predict candidate

sentiment with any degree of reliability. Pick a job applicant at random and there

is a roughly even chance that he/she will primarily motivated by any one of those

four key factors.

The conclusion is simple: in crafting an employee proposition, hiring managers

must now give equal weight to every aspect of a role. Yes, it needs to pay well, but

it also has to be a genuinely challenging opportunity with nice friendly colleagues

at a strong, culturally progressive brand. Easy, right?

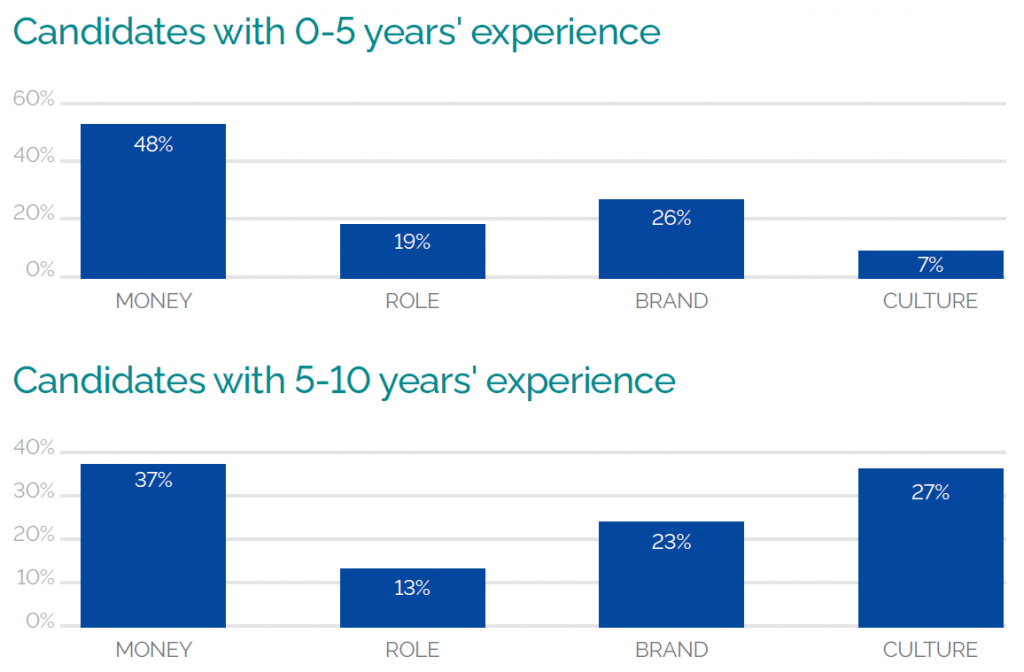

2. Although younger workers are the ones driving workplace evolution, they are

actually far more likely to be motivated by money; meanwhile older workers

place more value upon the role itself.

Social change is often created by the young. In the last half century or so, youth

movements have highlighted such important issues as racial justice, gender

equality and concern for the environment. In the corporate world, it is the junior

ranks who have most often agitated for a more caring and inclusive workplace. But

now they’ve got it, they don’t seem to want it very much. Or rather, they want other

things slightly more.

Among workers with fewer than five years’ experience, just 7% said culture was

their most important consideration when assessing a new job. In contrast, 48%

opted for money. Admittedly, the statistics shift slightly when we look at workers

with between five- and ten-years’ experience but even among this cohort money is

comfortably the most popular answer.

What are we to make of this? Surely it can’t be the case that every young person

who speaks up about culture and purpose is merely virtue signaling. No, a more

plausible narrative is as follows: Our least experienced cohort (those with five years’

experience or less) will likely be in their first or second job. They may have college

debts and they’re almost certainly paying high rents. Naturally, money is important

to them. In addition, being at the start of their career, they are likely to view their

current job as merely a steppingstone to better things. As a result, workplace

culture is less of a priority.

By contrast, older workers are likely to be homeowners, possibly with substantial

savings and relatively affordable mortgage repayments. So while money will be

important to them (they’re also likely to have kids and college fees), it won’t be as

urgent an issue as it is to a debt-ridden graduate. Also, having long since passed

the job-hopping phase of their career, older workers are more likely to view their

current role as a longterm thing. Ergo, they value it more highly.

3. Employer efforts around EVP may be misconceived if they’re simply aimed at

attracting talent: culture is the top priority of less than a fifth of our source pool.

Out Talent Intelligence practice has worked on dozens of perception analysis

studies, typically for clients who want to find out how their EVP lands with a

particular candidate pool. At the outset of every project, we ask the same question.

‘Why do you want to know this?’ Often, it transpires that the client believes they will

attract more and better candidates if their brand is associated with certain cultural

values.

Our experience is that this more often works in reverse. That is, a company with a

toxic culture will certainly fail to attract and retain top-level talent. But a company

with a strong culture will not be noticeably more successful in hiring people than

any of its competitors.

The results of our survey support this observation. Just 18% of the source pool said

culture would be their primary concern when considering a new job.

Of course, it’s important not to misinterpret that statistic. It does not mean that 82%

of workers don’t care about culture. It just means it’s not their first priority. In seeking

to explain this further, we can draw again upon multiple perception analysis

studies. One of the findings that emerges repeatedly from such projects is that

most people believe they already enjoy their working environment. They may not

be happy about every aspect of their job, but they typically think their employer is

fair-minded, inclusive and culturally progressive.

In other words, a good corporate culture is now considered a given, just like central

heating. You wouldn’t expect to attract more candidates because your office has

double glazing and adjustable thermostats; nor should you imagine your hiring

figures will significantly increase because you offer a gender-diverse workforce or

an active network of in-work support groups.

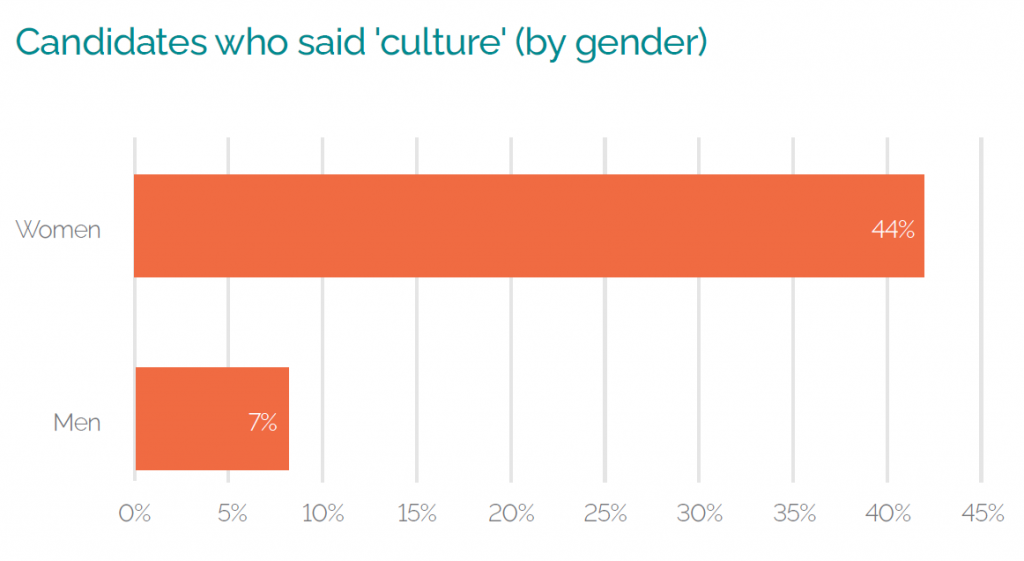

4. Women are far more likely than men to be motivated

by workplace culture.

Readers of our recent whitepaper ‘Is Hybrid Working?’ may remember an intriguing

anomaly between the way men and women view the new workplace paradigm.

Briefly, while male workers are more likely to want to work fully remotely, female

workers are more likely to want to work fully onsite. We mention this here because

it casts additional light on one of the findings of our latest survey.

As the graphics show, just 7% of male respondents opted for ‘culture’, but when

we filter instead for female respondents the figure leaps to 44%. That’s a massive

difference. But not perhaps surprising given many women’s preference to travel

into the office rather than work from home. If you plan – or at least prefer – to

operate from a laptop in your kitchen, it doesn’t really matter what the workplace

culture is like. You’re never there anyway. Conversely, if you’re in the office every day,

you’ll want it to be a nice, welcoming place.

It’s important not to generalize. We are not talking about most men or most

women. We are simply saying that a certain attitude or opinion is more likely to be

attributed to one or the other gender. The takeaway for recruiters is therefore one of

nuance. When seeking to close a female candidate, it is worth bearing in mind that

culture – even if it’s not their top concern – is likely to play a significant role in their

thinking. By contrast, efforts to secure a male candidate by repeatedly emphasizing

the corporate environment may constitute a tactical error.

Perhaps the best advice is to forget about the gender perspective and simply find

out your candidate’s opinion on remote working. Would they, for example, be happy

to work fully remote? If so, the concept of ‘culture’ probably isn’t that important to

them. If, on the other hand, they’d happily come into the office five days a week,

they’re probably someone for whom culture is a critical consideration.

5. Brand strength won’t hurt an employer but it’s unlikely

to mean you can hire top talent for less money.

Seasoned recruiters will remember a time when brand was king. Approach a

candidate with an opportunity to join a global player such as Citibank or Unilever

and you’d be guaranteed a positive response. But times have changed. The 2008

financial crisis reminded us that some corporate gods have feet of clay. Meanwhile,

the fintech revolution demonstrated that small is sometimes beautiful. Dial in

an increasing focus on diversity, sustainability and purpose – not values that big

companies always easily demonstrate – and it’s not surprising that ‘brand’ has lost

some of its lustre in the world of talent acquisition.

That’s certainly what our results seem to indicate. Brand is still a relevant

consideration for many – probably most – people, but it won’t often trump money

or a challenging, well-defined role. Hiring managers should take heed.

Any illustrious company seeking to undercut its competitors on pay and rely on its

brand to secure top talent, may be disappointed.

One suspects this is a lesson already learned by some of the tech giants. Netflix, for

example, is well known for paying well above market rates for the best candidates.

It’s also, we’d suggest, why many global companies seem to downplay their

success and present themselves as folksy, down-to-earth startups. Think Ben &

Jerry’s. In fact, you might almost say that the most farsighted companies are now

seeking to develop a sort of ‘anti-brand’. By stressing their commitment to mission

statements and corporate values, big companies are demonstrating a clear

message: they no longer take their employees for granted. Another way of doing

this of course is to pay those employees a lot of money